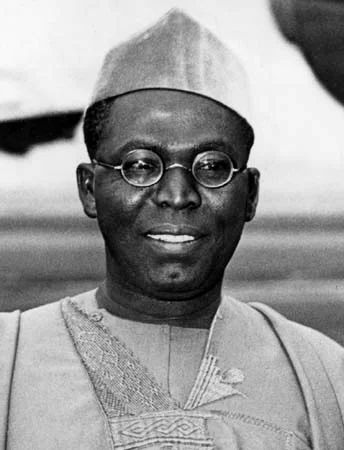

A lecture given Chief Obafemi Awolowo to students at the Adventist College of West African, Ilishan-Remo, on 27th January, 1961

As a politician, the object of my daily vocational pursuit is politics. But the forum on which I speak this afternoon is that of an Institution of Higher Learning, sponsored by one of the famous Christian organisations in the world. I thought, therefore, that it might be appropriate, from the points of view of myself and yourselves, for me to address you on `Politics and Religion’.

There are many popular misconceptions about politics. I will relate only some of those of them that have come to my knowledge, and will also endeavour to show that they aremisconceptions.

We all have heard it said times without number that `politics is a dirty game’. The description of politics as

a game is `a felicitous one, and it looks as if it is a contradiction in terms to daub a game as dirty. Speaking

generally, any game at all, other than a game of chance, is good.

But the manner of playing it may be clean or dirty, all depending on whether or not the players observe the rules for playing the game which mankind has laid down in conformity with universally accepted standards of decency and ethics. In other words, whether the game of politics is clean or dirty will depend wholly and solely on the manner in which a particular set of politicians play it.

Those who hold that politics is a dirty game have reasons for their contention. But we will presently see from these reasons that it is the manner of playing it that they have in mind and not the game itself.

First among the reasons is that politicians are in the habit of criticising — indeed attacking, abusing and vilifying — one another both in private and in public. A proper understanding of the nature of politics will show that criticism is indispensable to the game of politics and that abuse, attack and vilification are its inescapable incidentals.

Politics is the science or the art of the management of public affairs. It is now a far cry from the primeval days when the entire members of a society tried to take part in the management of their affairs. In modern times a breed of people called politicians have emerged who claim to have the necessary qualifications for the efficient management of public affairs. Except in a totalitarian community where sectarian views and ideas are regimented or forcibly suppressed, these politicians naturally form themselves into groups called parties each with different ideas of its own an divergent methods of realising those ideas. In a democratic

society, it is open to the people to entrust the management of their affairs to one or more of the parties for a

stipulated period of time. The party or parties thus chosen become the government, and more properly the trustees of the people, enjoined for their term of office to administer the trust

with absolute prudence, probity and public-spiritedness.

It will be seen from what I have said that the final arbiters of

whether the ideas and methods or policy and programme of a

political party are relatively superior to, and likely to be more beneficial than, those of others are the electorate, the voters.

In order to enable them to reach a verdict which is fair to the contenders and most likely to be in the people’s own best interests, they must have all the facts placed before them. The qualifications of each political party and of the individual candidates canvassing for votes on the platform of such a party must be established to the

satisfaction of the voters.

It is natural and legitimate for political parties to say the best they ever can about themselves and about the candidates they are sponsoring and to criticise one another most vehemently. The aim of healthy criticism is to spotlight defects and to prescribe means for removing them if that is possible. When the contending political parties do this honestly and conscientiously, the electorate are best placed to

make a choice which will rebound to the benefit of all.

In private life, before we entrust our personal or business affairs to anyone, we take steps to inquire into his

qualifications both as to competence and character. Such an inquiry as this is done in private, because what is at issue is a private concern. But the competence and character of politicians must of a necessity be examined in the full glare of public limelight Because what is at issue is the welfare of the community or nation. In the management of private affairs, a gross mistake would only affect the fortunes of one man or a family or a small group of persons. A serious error of judgement in the management of public affairs might adversely affect the lives and fortunes of millions of people.

For this reason, there is need for the competence and character of public men to be subjected to severer and stricter scrutiny — and that mainly in public — than those of persons engaged in private concerns.

Abuse or vilification in private or public life is to be deplored, because it stems from a. mind which is depraved and warped. But the community which a politician seeks to serve is an amalgam of saints and sinners, with a sprinkling of the former as against an over-abundance of the latter. The gentle rebuke and occasional eulogy of the one may be fascinating, but the constant tauntings of the other must be accommodated.

Politicians are born not made; and anyone who has not the stomach for the railings of the masses and is only interested in their occasional hosannas, has no right to enter into public life.

Another reason given in support of the charge that politics is a bad game is that good politicians are few and far between.

The general run of them are irredeemably mundane: materialistic, atheistic, immoral, ruthless and unscrupulous.

All the great religions as well as the lesser ones recognise the absolute need for a government among men. We all do. Furthermore, we realise that only a small number of people should be entrusted at any given time with the apparatus of such a government. If the persons thus chosen are bad, it is not because politics is bad. The fault is in the politicians, in the members of government, rather than in politics or government

per se.

The last of these popular misconceptions which I consider it worth mentioning in this talk is that Politics and Religion do not mix. Indeed, there are not a few who hold the view that Politics is so essentially materialistic and Religion so fundamentally spiritual that it is difficult for a man to be a successful politician and a good Christian at the same time.

I want to admit, without the least hesitation, that Politics is essentially materialistic and that Religion is fundamentally spiritual. But it cannot be gainsaid that living man is a combination of matter and spirit.

If a man is to live a full life and be the real image of God which he is intended to be, his Body — that is his brain and brawn — must not only be well-developed and healthy, but must also function in harmony with and under the control of his spirit or Soul. The Soul is ageless and pure, and does not need any development. But the Body must be trained, developed and disciplined to acknowledge both the existence and the supremacy of the indwelling Soul.

In the process of bringing out the best that is in man, and of enabling him to live a healthy and happy life, the agencies of Politics and Religion must work in close and harmonious co-operation. The eradication of ignorance, disease and want is a matter of the utmost concern to Politics as well as to Religion. As a matter of fact, in the early days the education of the young and old, and their health and general well-being were more or less the exclusive preserves of Religious Bodies and their offshoots and allies — the Charitable Organisations. In those olden times, the primary functions of Government (for the purpose of this talk I am equating Government with Politics) are the preservation of peace among the subjects at home, and the resistance of external foes. It is in modern times that Government has its functions beyond the limits of bare security for individual citizens, to

include their education and health; and their welfare and happiness.

In other words, Religion recognised from the beginning of times that unless the brain of a man is developed by education(secular and religious), and his body by physical exercise is well as by the nurture of good and adequate food, and by the comfort and self-respect of simple and neat clothing and shelter, man would be much more brutish and degraded than the lower animals. For His great purpose on earth, however, God needs the finest possible instrument, which is to be found in a healthy body and an enlightened and sane mind. For this reason, Religious Bodies down the ages have catered and still cater, in so far as their limited resources permit, for the material as well as the spiritual well-being of man.

The purpose of Politics is first and last the material well-being of man. The purpose of Religion, on the other hand, is to do this or to ensure by persuasion that this is done, and to cater in addition to the spiritual welfare of man. In many modern States, what we see is not a separation of Politics from Religion but a division of labour between them.

From what I have said, it will be seen that in modern times and in a democratic society, the functions of Politics

are complementary to those of Religion. I have used the phrase `in a democratic society’ advisedly. For in its attempt to evolve the best means of catering to the welfare of man, mankind has employed various devices. Some have turned out to he good whilst others are simply infernal. Examples of those that are in current use may be given: Democracy and Dictatorship; Capitalism, Socialism and Communism.

The terrestrial part of maxi is inherently selfish, tyrannical and corruptible. The ethereal part of man — that is the Soul — is pure, just, incorruptible, uplifting and ennobling.

Consequently, man is constantly subjected to internal conflict in which either the Body or the Soul must win. In the short run victory may go to the former, but in the long run it is the latter that tends to be on the ascendant.

It must be borne in mind that Communism or Marxism-Leninism which, in regard to the methods by which its declared

ideals are attained, is atheistic and evil, has dominated the minds and lives of more people than believe in Christ, and in the respect for human dignity which Christianity enjoins. This obvious ascendancy of an evil political system over the moral and ethical tenets of Religion is no evidence of antipathy between Politics and Religion. On the contrary, it is proof positive of the utter lack of spiritual discipline and of complete moral bankruptcy on the part of political leaders all the world over, and of want of dynamism and afflatus, and of exemplary leadership, on the part of Religious Bodies. Contemporary political circumstances demand that Religious leaders must recapture and relive the great and noble ideals and the militancy of those inspired and immortal Prophets, Apostles and Evangelists who had the divine courage to proclaim the truth as God gives it to them to know the truth, and to call cant, humbug, political murderers, and brutes and devils in human flesh, by their

proper names.

Apart from both being complementary, it will be seen from what I will say presently that the best in politics derives from and is firmly rooted in religious ideals. Four examples are enough to establish this assertion.

First, one of the aims of Religion is to teach a man to love his neighbour as himself and to do unto others as he would like them to do unto him. We are also taught that God is no respecter of man. All are equal before Him. It is a fundamental principle and an accepted practice under a good government that all citizens are equal in the eye of the law, enjoying and rendering reciprocal rights and duties. Negatively, every citizen is forbidden, under pain of legal sanctions, from so conducting his affairs that he becomes a nuisance or a menace to his neighbours. Positively, under law he must so live his life that he is at peace at all times with his fellow men.

Second, in all great religions, women are treated on the basis of equality with men. Our Lord Jesus Christ is the

most outstanding exemplar in this respect. Today, politicians all over the civilised world are eloquent in their advocacy for equal treatment for all persons irrespective of sex.

In doing so, they are merely reflecting in public life the unparalleled example of our Lord.

Third, many of the Fundamental Human Rights, particularly the three Freedoms of Conscience, of Association and

of Speech, have their origin in the great Religions. Many Prophets, Saints and Evangelists have suffered pain or death because they have dared to exercise their freedom of Conscience and of expression. It was for this noble and imperishable cause that John the Baptist was executed, that our Lord Jesus Christ was crucified, and Mohammed for a while fled his home in Mecca. Many great names in Politics drawing their inspiration from Religion also suffered or died for the same cause. It was for this cause that Socrates was

sentenced to drink the hemlock and to death.

Fourth, in my considered and settled opinion, the best, political ideal for mankind is Democratic Socialism which is founded, among others, on the principles of the well-being of the individual, and brotherhood among all men irrespective of creed, colour and race. The fundamental concept of socialism is: `From each according to his ability and to each according to his need.’ This concept has its root in the teachings and practices of great Religions through the ages.

Thus far I have endeavoured to show that Politics is not only complementary to Religion but also that the most

beneficial political system derives its strength from the tenets and practices of the great Religions.

Except under Communism where Religion or Belief in God is suppressed, and unless we wished to revert to Theocracy

which has long been out of fashion, Government (and hence Politics) and Religion must exist side by side working

hand in hand for the good of man. The tragedy of these modern times is that in some cases there is so much lack of

understanding among some religious leaders that they are intolerant of some of the manoeuvres of politicians. In other cases, religious leaders have allowed themselves to be completely subordinated to governmental institution to the extent that some Religious Organisations are mere arms or projections of the Government.

Religious leaders need not be intolerant of politicians or of their manoeuvres for vantage position. Our Lord lived in an age of political intrigues and tyranny of the worst kind. Yet He did not hesitate to say in reply to his tempters, `Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.’ There is more meaning to this famous saying of our Lord’s than a brilliant display of wit or a shattering out-manoeuvring of His adversaries. He does mean that His bearers should obey God as well as Government which is the constituted authority for the management of material human affairs. But since the earthly authority is ordained by God, it is easy to infer that where Caesar’s behests are manifestly repugnant to the injunctions of God, the latter must be made to prevail whatever the consequences. A Christian must, however, seek by Christian methods to make the Will of God sovereign and supreme m the society where he lives. The aim of Religion is the dissemination of truth — truth about the Will of God for the guidance of man. To know the truth and to uphold it is the only sure avenue to freedom and happiness.

It follows that in order that it may discharge its functions, a Religious Organisation must be independent of Government and its patronage and must never be subordinated to its dictates or whims. Otherwise, the sole compass by means of which the masses of believers must be guided in their Spiritual pursuits on the confused and stormy ocean of life becomes thwarted and unreliable. A Religious Organisation should never allow itself to be regarded as the mouthpiece arid instrument of the powers-that-be. If it did it would sink or swim with the Government concerned; and in any case it would no longer be well-placed to tell the truth as it knows it. It is incumbent upon Government and politicians to conduct their affairs in strict accordance with religious teachings and ethical standards. `Nothing is politically right which is morally wrong,’ says Daniel O’Connell. Therefore, when politicians do the right they can rest assured that they will be covered in a favourable manner by the non-partisan detached and fearless pronouncement of religious leaders of undoubted uprightness and godliness.”

Credit : Chief Dele Momodu